Think Twice About Those Traps

By Denys Hemen, Hospital Manager

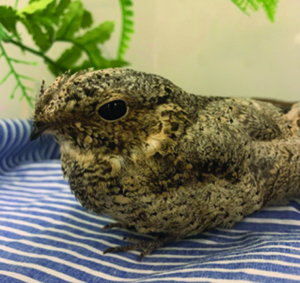

Bewick’s Wren on fly trap

There are dozens of home pest control items available for purchase today at various home improvement retailers. From sprays to traps to zappers, humans have developed many creative ways to keep unwanted insects and rodents out of our homes. It is understandable for people to strive to keep the inside of homes free of unwanted creatures. Unfortunately, when these products move from indoor pest control isles to the outdoor gardening section in retail settings, this becomes a misguided and irresponsible action. Native and beneficial wildlife often become the unintended victims of these products. The worst items to place outdoors are poisons, glue traps, and snap traps.

When poisons are moved outside of the home, the number of non-target species that are affected increases exponentially. Poisoning rats and mice outside may lead to predator species like coyotes, bobcats, and raptors eating these sick and debilitated rodents that are easy to catch. Many health problems may arise, such as raptors losing the clotting ability of their blood and damage to the immune systems of coyotes and bobcats which may lead to severe break outs of mange. Such problems are seen inside of the hospital at CWC many times a year.

Glue traps, including sticky fly traps, used outside of the home draw in even more non-targeted animals. Sticky traps are a double whammy because the target species gets trapped in the goo and predators will go after it, entangling themselves in the sticky mess. The intention of the glue trap is to keep prey in place so that they slowly die of dehydration and starvation. Also, animals may accidentally get stuck while going about their natural ground or arial foraging routines. We have seen all types of animals stuck in these traps. Snakes, ground dwelling birds like towhees and wrens, mockingbirds, warblers, desert cottontails, and many other species have passed through the doors of our exam room with feathers, scales, or fur entangled in a sticky trap.

A very wide variety of domestic and wild animals are harmed by snap traps left outside. A rat snap trap has the potential to cause great injury to a curious cat or dog that may sniff around the bait. Wild animals fare even worse. Just last month we received an American Crow that had its beak shattered by a snap trap as well as a Barn Owl with a trap on its leg. Unfortunately, neither patient survived their injuries. An earlier snap trap victim, a Striped Skunk, was able to be treated and released with 51 days of medical care after getting his foot caught in a rat snap trap.

Coyote pup with mange

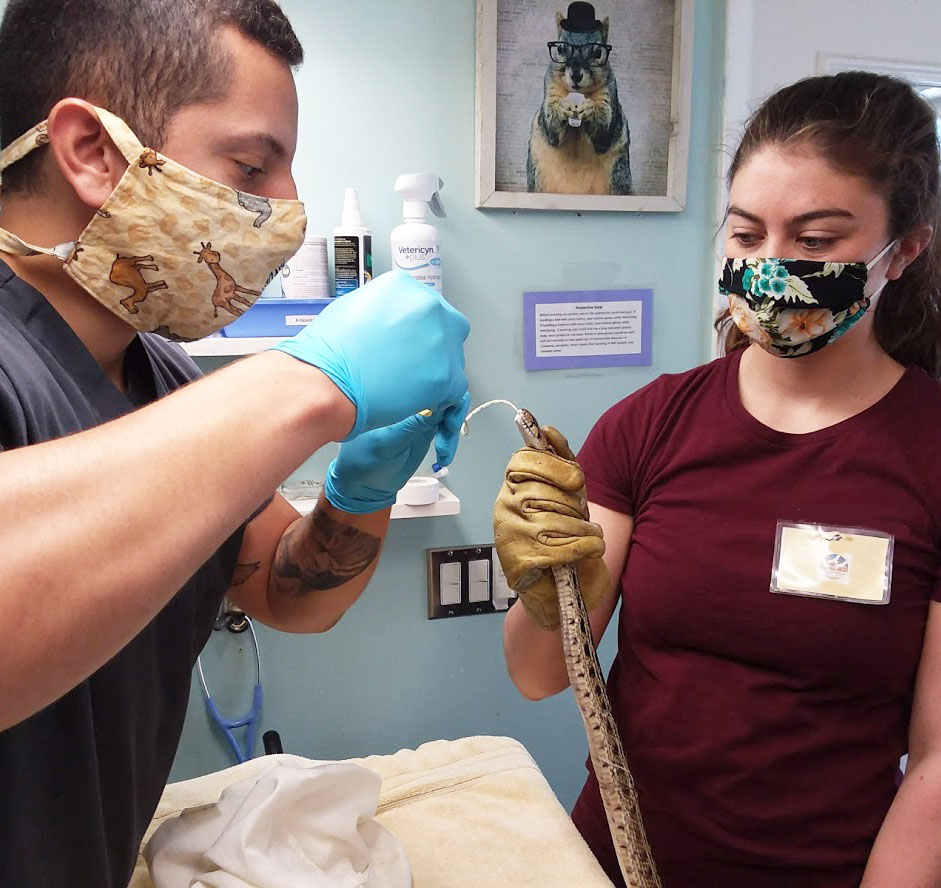

Directly after the operation, he was taken to CWC for rehabilitation and assigned Wildlife Technician, Cambria Wells, to be his caretaker and monitor his recovery and help him gain some weight back. CDFW and ESRP also wanted to be certain that he could capture his main dietary staple, the kangaroo rat, and that he could fully open his jaw. Over the course of 12 days, we kept a close eye on his sutures, his body weight and body condition, and his demeanor. Luckily for us, he was an easy patient with a quick recovery and a great appetite! During his stay at CWC, we had daily communication with Drs. Pyrdek and Eng, the biologists with ESRP, and CDFW. Their advice was instrumental in his quick recovery!

Directly after the operation, he was taken to CWC for rehabilitation and assigned Wildlife Technician, Cambria Wells, to be his caretaker and monitor his recovery and help him gain some weight back. CDFW and ESRP also wanted to be certain that he could capture his main dietary staple, the kangaroo rat, and that he could fully open his jaw. Over the course of 12 days, we kept a close eye on his sutures, his body weight and body condition, and his demeanor. Luckily for us, he was an easy patient with a quick recovery and a great appetite! During his stay at CWC, we had daily communication with Drs. Pyrdek and Eng, the biologists with ESRP, and CDFW. Their advice was instrumental in his quick recovery!