By Brittany Moser, Wildlife Technician

One-week-old Mule Deer fawn

Mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) are named for their large mule-like ears that can rotate and move toward sounds like little satellite dishes detecting precise locations of sounds to escape danger. They flee with high jumps, leaping and landing on all four legs. Mule deer are spread across the Western United States and are native to California. They are herbivores, typically consuming 90% of their diet from shrubs, leaves, and occasionally berries and acorns. These herd animals are commonly found in an oak woodland or hillside terrain habitation and are most active around dawn and dusk.

California Wildlife Center is the only facility authorized to care for orphaned, sick, or injured mule deer fawns in Los Angeles County. Fawns are born in late spring through mid-Summer when a female doe gives birth to one or two fawns. They are born covered in spots and scentless in order to remain camouflaged and spend most of their day hiding from predators while their mother is out foraging for food. Fawns typically stay near their mothers and continue to nurse throughout their first year of life. In the Spring, we receive many calls about fawns that are all alone, however, in most cases they don’t need to be rescued as the finder is not aware that the mother is simply grazing nearby, and the fawn is not abandoned.

We currently have six mule deer fawns in our care. One patient from Lompoc was found abandoned near a quarry, stuck in mud and unable to move for two long days. That fawn arrived malnourished, lethargic, and suffering from a respiratory infection. Another fawn was found along a bike path, calling out desperately next to their deceased mother, and a few were found wandering alone.

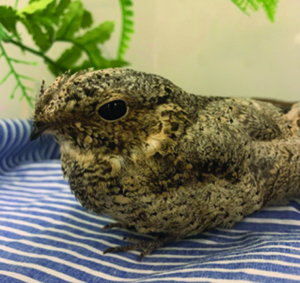

Four-week-old Mule Deer fawn

When a new fawn arrives, we move them into a quiet warm area to allow time to acclimate from the stress of transport before performing a thorough exam. During the exam we keep their eyes covered to minimize stress since they are susceptible to capture myopathy and may easily die from stress. During their first two days, we provide supplemental fluids and colostrum. Colostrum is the doe’s first milk – high in protein, nutrient dense and full of antibodies that help protect the fawn from contracting disease during their first week of life. They are also initially given goat milk, as it closely resembles their natural milk composition. New fawns are quarantined in a separate area for at least one week while we run fecal exams and treat any illnesses or injuries before combining with our other fawns in order to prevent the spread of disease.

We limit human interaction while working with the deer by wearing camouflage hooded ponchos and observing them using installed cameras throughout their enclosure. The restricted contact is important when raising young fawns to cultivate their wild instincts and natural fear of humans. New fawns are bottle fed and quickly learn to drink off a bottle rack. This decreases human contact during feeding and prevents an association with food and people.

Once rack trained, they are moved to a larger outdoor enclosed area with other fawns where we provide fresh foliage, a specialized dry diet, and water. We use secret latch doors and chutes while feeding the fawns in order to limit interaction with them.

The Lompoc fawn has fully recovered and currently in this enclosure with other fawns happily prancing around snacking on rose petals and grape leaves, their favorite! When the fawns are old enough, we will open a gate that leads to an outdoor enclosure that resembles their natural habitat. Mule deer fawns are released on site in the beautiful Santa Monica mountains. We supply them with fresh food and water for a period of time while they acclimate to their new wild life.