Meet Patient 1311: A Comprehensive Care Success Story

by Jennifer Brent, Executive Director

You have heard their calls and seen them soaring high above the oak forest here in Southern California. These hawks are common across North America, though those found in California tend to be redder than elsewhere.

It’s only seven months into 2018, and it seems likely that the year is going to bring us an unprecedented number of Red-shouldered Hawks. So far, we have seen 12 of these majestic patients, in comparison to the last two years’ numbers of 15 and 17 admissions.

On May 7, Patient 1311, a Red-shouldered Hawk unable to fly, was recovered—literally–on Van Nuys Boulevard in Pacoima and brought to the East Valley Animal Care Center, where one of our volunteers picked her up. Upon arrival, staff veterinarian Dr. Stephany Lewis determined that the bird had suffered a left midshaft major and minor carpometacarpal fracture (in humans, a break near the wrist, where it meets the hand on the thumb side). At just 436 grams (slightly less than one pound), she was also underweight.

The next day, she was given pain medication and splinted. A few days later, she was anesthetized so that the area could be cleaned and the broken bones pinned, and she was given more analgesics and antibiotics. On CWC’s use of pharmacology in birds, Dr. Lewis states, “Our avian patients are placed on many of the same medications that are prescribed to dogs, cats, or even humans. Due to the physiology of birds and their much higher metabolic rate, often the doses are quite different. Dosing medications, particularly pain medications, for the number of species we see here can be a real challenge. This is an active area of study, so we are always trying to stay on top of the latest research.”

In wildlife medicine, we are often called upon to anesthetize animals for exams, because of the incredible stress they experience and for the safety of the handler performing the requisite intensive palpitating. A week after pinning, Director of Animal Care Dr. Duane Tom again anesthetized Patient 1311 for an exam to ensure that the pins were still in place. Three weeks later, because of excellent progress, Dr. Tom again anesthetized her to remove the pins. The wing was then wrapped to continue healing.

The Red-shouldered Hawk continued to recover well, showing good appetite and range of motion. The vets decided that she was ready to move to a lower enclosure that allows for more space and freedom, to begin physical therapy and desensitization to humans. The wing wrap was removed, and she was transferred to a lower enclosure on June 21. There Hawk 1311 was soon seen to fly on her own for the first time since being in our care. Her initial flights showed that she was able to gain good height but was somewhat crooked in flight.

The Red-shouldered Hawk practices her flying. Photos by Paul Simon Needham

On July 13, Diana Mullen, a highly-experienced volunteer who assists us by creancing injured birds, took her out for a test flight. Creancing involves attaching leather straps (jesses) to the bird’s lower legs and then attaching these jesses to a line up to 300 feet in length. Though tethered to the handler, the bird is still able to gain altitude, bank, and land on her own. For birds who have been with us for an extended period of time, these flights prove invaluable to progress, determining any muscle atrophy as well as serving as an assessment of the ability to thrive once released. On her first test, Hawk 1311 flew three times with great symmetry, which boded an excellent prognosis. The next day, Diana again flew her; she continued to make excellent progress.

Because of some damage to the feathers during surgery and while the wing wrap was in place, Hawk 1311 became a candidate for imping, the surgical replacement of damaged or missing feathers with healthy ones; this allows for release while new feathers grow in.

While all these measures taken together might seem rather extreme, they are fairly standard for a raptor that comes to California Wildlife Center with an injury of this type. In our years of experience, we have learned that comprehensive care from exams, surgery, rehabilitation and physical therapy ensures the best chance of a successful return to the wild.

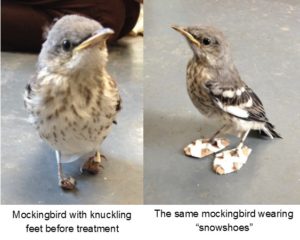

the bird to have to stand on the tops of her toes which were curled under and causing her additional injury.

the bird to have to stand on the tops of her toes which were curled under and causing her additional injury.