The Many Species of Orphan Care

By Cambria Wells, Wildlife Technician

California Towhee Fledgling Photo by Brittany Moser

The rest of the world might have four seasons, but wildlife rehabilitation has even more. Busy season at California Wildlife Center begins with the opening of the Orphan Care Unit when squirrel kits, opossum joeys, and dove squabs begin to trickle in. We never know when the moment will strike, but it’s not long before everything changes again.

Oak Titmouse and Western Bluebird Fledglings

Photo by Cambria Wells

At the end of May, we’ve settled firmly into baby bird season, with a wide variety of species residing in Orphan Care and others moving into outdoor enclosures to strengthen their flight and condition for release. Our first songbirds are Northern Mockingbirds, California Towhees, House Finches, and Lesser Goldfinches, common backyard birds here in Southern California that quickly run into trouble with tree trimmers, outdoor cats, and windy day accidents. Next, we begin to see American Crows and Common Ravens, favorites of many CWC volunteers. After these familiar visitors arrive, we can never predict which other species will come in.

In 2017, the Orphan Care Unit was overwhelmed with a flood of young Northern Mockingbirds. In 2018, we provided supportive care to a large number of House Finches. Thus far, 2019 appears to be the season of variety. Orphan Care has already treated a number of species such as the Oak Titmouse, Western Bluebird, Bullock’s Oriole, Dark-eyed Junco, Black-headed Grosbeak, and more. Each of these species requires different care, from the unique nesting needs of Cliff Swallows and Wrens to the particular eating habits of Towhees and Bushtits. Some also enter into care with gastrointestinal parasites or wounds which require medical treatment. Volunteers and staff work each day to provide these birds the nutrition and stimulation they require, rapidly adapting to changing circumstances and patients.

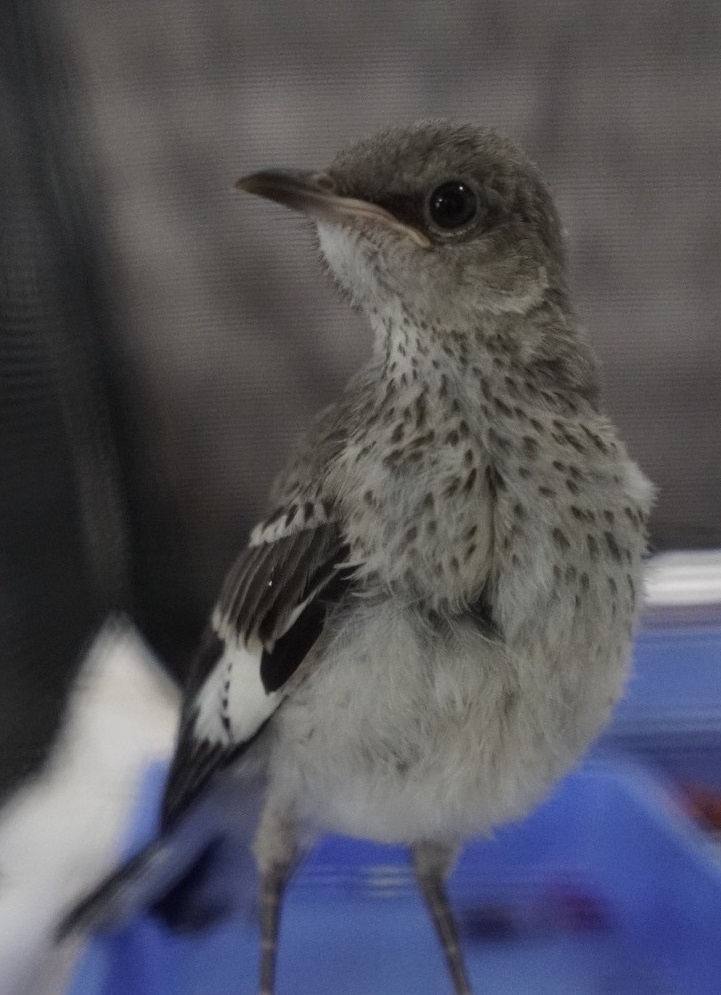

Bushtit Fledgling

Photo by Brittany Moser

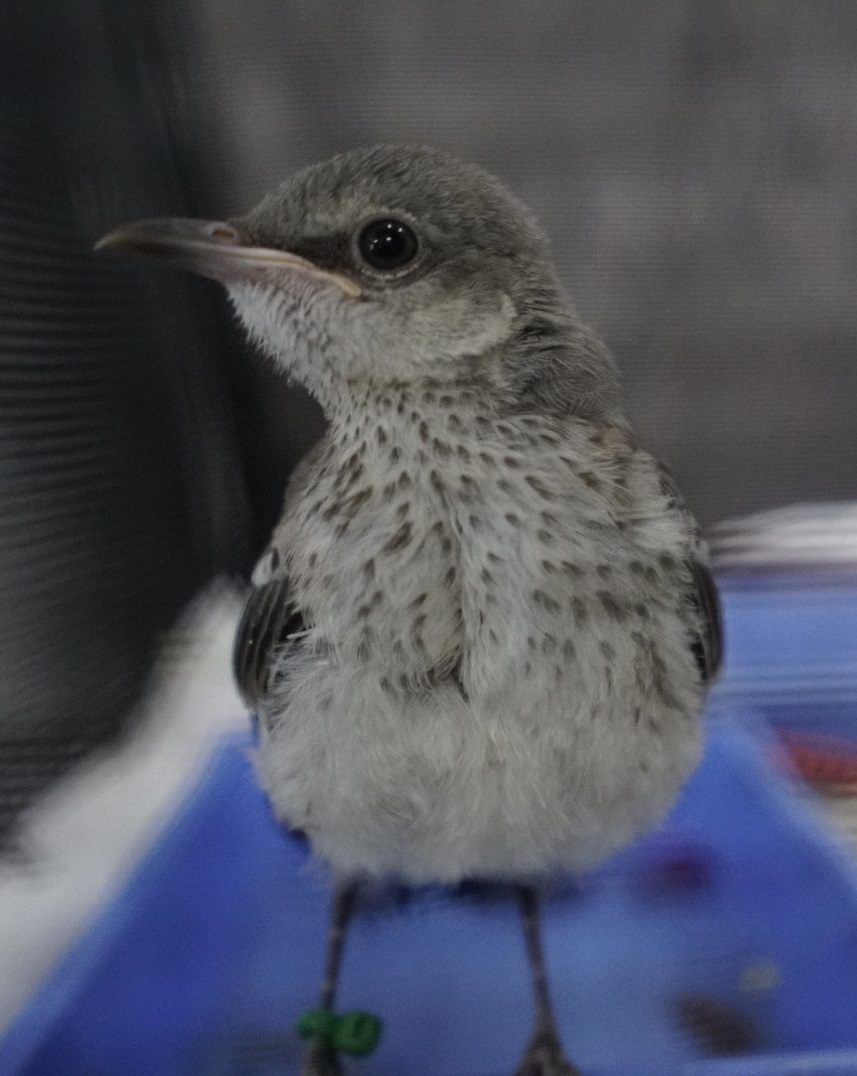

Black-Headed Grosbeak Fledgling

Photo by Cambria Wells

Over one weekend, the Orphan Care room can change completely, and your favorite patient can go from a nestling to a fledgling seemingly right before your eyes. In the two weeks a patient spends conditioning for release in an outdoor enclosure, they become completely independent, and their releases are a bittersweet victory. As each round of young animals moves on, we turn to the next and alter care to meet their needs again. The precious privilege of being involved in the early life of orphaned wildlife is only outweighed by knowing release means they’ll have a chance to raise their own young someday, in the wild, where they belong.